Share Album

- Run Time: 70.15

- Release Date: 2011

- Label: Naxos

- ASIN: B004GX91WA

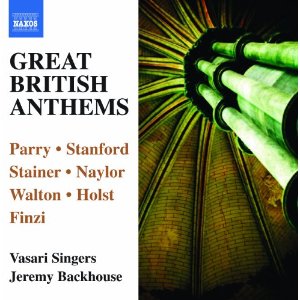

Great British Anthems

£7.50

Delivery is charged at current Royal Mail prices. FREE on all orders over £30.00.Dispatched within 2-4 days of purchase.

- Blest Pair of Sirens C. Hubert H. Parry 11:33

- Magnificat in B-Flat Major, Op. 164 Charles Villiers Stanford 11:59

- I Saw the Lord John Stainer 7:05

- Vox Dicentis: Clama E. W. Naylor 8:50

- The Twelve William Walton 11:31

- Nunc dimittis Gustav Holst 3:21

- Lo, the full, final sacrifice, Op. 26 Gerald Finzi 15:34

Album Details

A powerful series of some of the Anglican tradition’s finest anthems.

Reviews

- Great British Anthems – American Record Guide - These are accomplished performances of demanding repertory.

Special compliments must go to organist Jeremy Filsell for his brilliant and sensitive playing of accompaniments that require a high degree of virtuosity. Listeners who are looking for a program of this sort will not be disappointed.To read the complete review, please visit American Record Guide online.

American Record Guide

- Great British Anthems – MusicWeb International (2nd Opinion) - The music on this disc represents the English church music tradition at its finest and the performances are admirable.

This programme includes some of the most glorious anthems in the English church repertoire. It opens with Parry’s magnificent Milton setting – in my humble opinion, one of the finest of all English anthems. Organist Jeremy Filsell plays a key role in the success of this performance and I was pleased to note how properly attentive he is to Parry’s dynamic markings. So, for example, the very opening is loud, as it should be, but by bar 7 Filsell has reduced the volume significantly, as Parry requires. I admired also the way in which he brings out so much of the detail in Parry’s writing – notice the little subsidiary figures in bars 10 and 12, for instance.

Broadly, Jeremy Backhouse ensures that the performance follows the composer’s directions, though I was a little disappointed that he doesn’t appear to move the pace forward when the choir goes back into eight parts at “To live with Him” (8:58). I see that my colleague, Kevin Sutton, was troubled by an excessively bright-toned tenor in this piece (review). I agree that the first tenor part does come through at times, though I didn’t find this happened to such an extent that it marred my enjoyment. What I did feel, however, was that the alto lines and, even more so, the bass parts, didn’t register quite as strongly as I would have expected. In this piece Parry’s part-writing for all the voices is wonderful but both the first tenors and first sopranos spend a lot of time in their upper ranges. I wonder if the problem in this performance is that the lower parts – alto and bass – are a little under strength numerically? I don’t know how many singers were involved in this recording but the rather distant booklet photograph suggests a choir of between thirty and, at most, forty voices and for much of the work Parry writes in eight parts.

Both in the Parry and in the Stanford Magnificat that follows – and which is also in eight parts – the choral sound is often quite bright. I think both composers gave their sopranos and tenors prominent lines but did so in the expectation that the choir would be evenly balanced. For whatever reason it doesn’t seem to me that the lower voices in the Vasari Singers register quite sufficiently in these two pieces though, oddly, I found the remaining works in the programme were satisfactorily balanced. Overall, I enjoyed both the Parry and Stanford’s fine a cappella Magnificat very much. In the latter I liked the energy that the singers bring to the more extrovert passages, such as the opening and ‘Fecit potentiam’, but I also admired the way in which the several more reflective stretches of music were shaped.

Stainer’s anthem is no masterpiece – it’s music of its time – but both choir and organist are appropriately assertive at the start – and the choral bass line is more satisfyingly in evidence. Later on, the lyrical section (“O Trinity, O unity”) is launched beautifully by the sopranos and the other sections follow their lead as they join in one after the other. The anthem by Edward Woodall Naylor – why didn’t Naxos give his full name? – offers some dramatic opportunities, which the performers grasp. However, I particularly admired the way in which Naylor’s use of contrast is brought out in this performance. The lovely final pages feature a delicate soprano solo and, at the very end, a pleasing light tenor soloist makes his mark.

Unfortunately Naxos don’t supply any texts – these are available from their website, but that’s not the same as having them readily accessible in the booklet. This is a particular handicap in the Naylor and Finzi pieces, both of which have unfamiliar words, the former in Latin. It’s even more of a handicap in the case of Walton’s The Twelve, ‘An anthem for the Feast of any Apostle’, since the text is a complex one by W.H. Auden, which one really needs to follow. In his note, Jeremy Backhouse suggests, quite fairly, that the piece might be regarded as a mini-Belshazzar’s Feast. I know what he means. The men deliver the opening declamation powerfully and the whole first section, which has several dramatic moments, is well done by the choir. Here, and throughout the work, Jeremy Filsell gives a marvellous account of the demanding and vital organ part. The reflective central section (between 4:43 and 7:33) features excellent contributions from two soprano soloists.

The programme starts with a masterpiece and closes with another in the shape of Finzi’s Lo, the full final sacrifice. The mysterious opening is rendered with the utmost sensitivity by Jeremy Filsell. For me, this organ introduction seems to conjure a vision of a church interior illuminated by shafts of afternoon sunshine, perhaps cutting through traces of incense lingering from an earlier service. That’s just what is achieved here before the choir’s first hushed entry. The piece is very complex with many changes of tempo and metre. In a successful performance all these changes should be achieved seamlessly, so that the listener can concentrate on the beauties of Finzi’s harmonies and melodic lines and on Richard Crashaw’s synthesis of words by Aquinas. Judged by that criterion, this is a successful performance. It’s also successful in terms of the excellence of the singing and playing and once again Jeremy Backhouse ensures that his performers obey the composer’s instructions. A good pair of soloists, tenor and baritone, deliver the duet “O soft, self-wounding Pelican” very sensitively (10:23) and the final, seraphic 8-part Amen (from 14:36) is beautifully achieved.

The music on this disc represents the English church music tradition at its finest and the performances are admirable. I have not spotted the Vasari Singers in the Naxos catalogue before now so perhaps this release marks the start of a new partnership between this very proficient choir and one of the most enterprising labels around. We must hope so. In particular, it would be very good news if Naxos were to expand further their already excellent support for recent British choral music by inviting the Vasaris to record the Requiem for unaccompanied choir by Gabriel Jackson, which they commissioned and first performed a couple of years ago. I’ve not heard that piece yet but the other choral music by Jackson that I’ve heard to date makes me think it could be a significant addition to the CD catalogue.

John Quinn

MusicWeb International - Great British Anthems – Muso Magazine - "...the glorious textural colours combined with the traditional church location make for a heavenly blend."

Under the leadership of renowned conductor Jeremy Backhouse, the Vasari Singers have thrived for more than 30 years as one of the most celebrated and versatile chamber choirs in the UK. Since forming in 1981, the singers have concocted an extensive discography including their highly acclaimed 2007 release of Francis Pott’s major work, The Could of Unknowing.

Great British Anthems features some of the – yes – greatest works for chamber choir by 19th- and 20th- century composers, including Parry, Holst and Walton, as well as texts from (the Italian priest and theologist) St Thomas Acquinas, John Milton, WH Auden and the Bible. These ‘British’ anthems were created during the genre’s golden era; that is, when ceremonial music instilled with pomp and jubilance was the foundation of the choral empire.

The almost elitist weight that choral music carried allowed composers to indulge, and that bombast is certainly evident here. We begin in the 19th century with Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens, a work that established him as the leading choral composer of his day. The Vasaris are perfect for such luxurious music – the glorious textural colours combined with the traditional church location make for a heavenly blend, and Stanford’s unaccompanied Magnificat for Double Choir exemplifies their talent perfectly. Walton’s masterpiece The Twelve is the youngest of the 20th-century choral works. Almost avant-garde in style in comparison to the elder pieces here, its virtuosic organ part boasts the superb talent of Jeremy Filsell.

Francesca Treadaway

Muso Magazine - Great British Anthems – MusicWeb International - Ravishing is as good a word as any to describe this splendid performance that achieves near perfection.

Hubert Parry is best known for his coronation anthemI was glad,and for his hymn tuneJerusalem,a setting of Blake’s magnificent poem. The hymn alludes to the legend that Jesus spent time in England during the undocumented years between his childhood and the beginnings of his ministry in and about his homeland.

Parry is sadly underrated today, even though he composed a number of fine symphonies that are on a level with Elgar and dare I say it, even Brahms. He is represented here byBlest Pair of Sirens,to a text by John Milton, a less often performed, but no less glorious work than those aforementioned. Alas, from a disc of otherwise quite outstanding performances, this rendition is found wanting. The booming acoustic, the thundery organ and a general lack of attention to enunciation render the text of this marvelous work unintelligible. Add to the fray a wayward member of the tenor section whose overzealous brightness of tone sticks out like a badly-voiced reed stop, and you get a performance that leaves something to be desired.

Now that those quibbles are out of the way, we can get on to what is one of the finer choral recordings that have crossed my desk in some time. Stanford’s rich double choir Magnificat, dedicated to the memory of Parry, with whom the composer had a longstanding and sadly unresolved parting of the ways, receives a splendid performance with all the elements of clarity, intonation, balance and tone in place.

John Stainer is ridiculed today as the apex of Victorian bad taste. But in spite of his rather trite and passé style, he should be remembered as a fine teacher and scholar, and as an organist and choirmaster who helped to revolutionize Anglican church music.I saw the Lord, is a diehard favorite and here receives a clear and unaffected performance by the Vasari Singers.

E.W. Naylor was primarily a composer of operas, and hisVox Dicentis: Clamaviof 1911 reflects his dramatic flair. My reaction to this work has always been “oh yeah, I sang that piece once.”Although it is flashy, I have never found it to be particularly memorable. The Vasari’s performance is stately and without undue affect.

Walton’s music is marked by taut rhythms and spicy, jazz-influenced chords.The Twelve,with a text by the oft-acerbic W.H. Auden is typical Walton with splendidly biting harmonies and jaunty off beat rhythmic gestures. Again, the Vasaris do not disappoint with a finely hewn performance that captures all of Walton’s seriousness deliciously offset by wit.

Holst’s gloriousNunc Dimittislay fallow for many years until it was rediscovered in the 1970s and thankfully restored to the repertoire. It is distinguished by a splendid cascade of vocal entries marked by shimmering harmonies and a most sensitive setting of the text. My only beef with this performance is that it seemed a bit rushed. There could have been more time for the lush chords to settle into place. I also felt that the ending was a bit to edgy in its loudness.

Gerald Finzi lived all too short a life for one so very gifted. His epic motetLo, the full final Sacrifice,shows him in his finest hour. It is a masterpiece, a perfect union of music and word and is abundant in simply ravishing sounds. Ravishing is as good a word as any to describe this splendid performance that achieves near perfection. Mr. Backhouse leads a seamless performance of a work that can be maddeningly “sectional” when in the wrong hands. This fine rendition is worth the very affordable price of the whole disc.

To sum it all up, this is a collection of great standards that on the whole is left in very able hands. The flaws, although distinct, are few enough not to detract from what is generally some very fine singing indeed. Organist Jeremy Filsell is up to his usual fine standards with sensitive registrations and technically flawless playing.

Kevin Sutton

MusicWeb International - Great British Anthems – Gramophone - A powerful series of some of the Anglican tradition’s finest anthems

The Vasari Singers under their founder, Jeremy Backhouse, here demonstrate their versatility in a wide-ranging collection of anthems designed for Anglican worship. Though Backhouse has female sopranos and altos instead of the traditional boys’ voice, their timbre is always fresh and bright, and apt for this music.

The opening item, Blest Pair of Sirens is Hubert Parry’s best-known anthem, a rip-roaring setting of John Milton’s poem “At a solemn musick”. It is introduced by an elaborate organ solo, and though the organ sound is rich and full on the disc, the reverberant acoustic of the beautifully restored Chapel of Tonbridge School muddies the result. Happily, the fine precision of the choir’s ensemble cuts through the sound to make it a powerful introduction to the collection.

Written in 1889, early in Parry’s career, it was dedicated to Stanford, who is here represented by one of his most elaborate settings of the Evensong canticle, the Magnificat for double choir. The Vasari Singers relish the complexities and go on to the much simpler and more direct choral setting of Stainer in the anthem I saw the Lord, dating from much earlier, 1856.

EW Naylor (1867-1934) is the least-known of the composers represented, yet his 1911 anthem Vox dicentis is among the most striking of those here with its dramatic and extreme dynamic contrasts, beautifully realised. That leads to the most distinctive item of all, Walton’s anthem The Twelve, set to words expressly written by WH Auden, like Walton associated with Christ Church, Oxford. It is not an easy sequence to hold together but Backhouse does wonders in achieving what he describes as “Belshazzars’ Feast in miniature” with choral writing just as memorable in jazzy syncopations.

Holst’s setting of the second Evensong canticle the Nunc Dimittis was discovered among the composer’s papers long after his death and is one of the most beautiful items here, leading to Finzi’s Lo, the full final sacrifice, written in 1946 in the aftermath of the Second World War. Commissioned by Walter Hussey for St Matthew’s, Northampton, it sets a text by Richard Crashaw based on a passage from St Thomas Aquinas and ends with a sublime setting of the Amen, a fitting conclusion to this very satisfying selection of anthems, essential listening for anyone fond of Anglican church music.

Edward Greenfield

Gramophone